A Statement of Work (SOW) is a project's rulebook. It's a legally binding document that details the activities, deliverables, and timetable. It is the blueprint that defines everything agreed upon between a client and a service provider, setting the terms for the project.

What a Statement of Work Actually Does

An SOW is more than paperwork; it’s an agreement that prevents misunderstandings. Its main job is to get everyone to agree on what a successful project looks like.

If a project is like building a house, the SOW is the architect's plan. It specifies what will be built, how it will be measured, and when it will be finished.

This document serves a few practical functions:

- It stops scope creep. By defining what’s included (and what’s not), a good SOW prevents gradual, unapproved additions that can derail a project.

- It clarifies expectations. From payment schedules to reporting requirements, it leaves little room for assumptions.

- It provides a legal framework. As a signed contract, it protects both parties by laying out obligations and deliverables.

- It guides the project plan. Project managers use the SOW to build schedules, allocate resources, and measure progress against a baseline.

SOW vs Proposal vs MSA

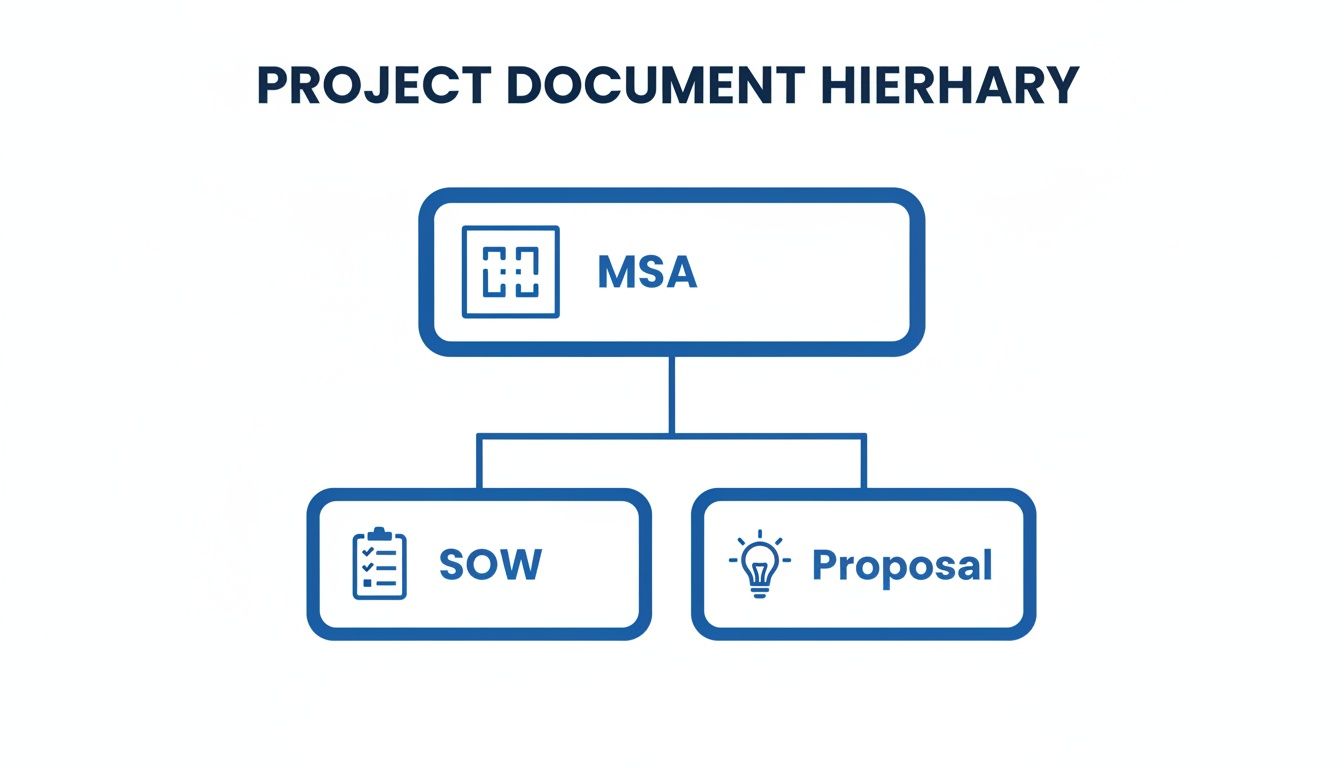

A Statement of Work is often confused with other business documents, like a proposal or a Master Services Agreement (MSA). They work together, but they have different jobs.

A proposal is a sales document, designed to persuade a client. An MSA is a broad contract covering the long-term legal relationship between two companies. The SOW contains the specific details of a single project.

An SOW is a detailed component that often sits within a larger service agreement, laying out the work to be delivered. The MSA might say, "We will provide general IT services," while the SOW gets specific: "We will migrate 50 user accounts to the new cloud server by June 30th for €15,000."

A project without a solid SOW is like a journey without a map. You might get somewhere, but probably not where you intended, and it will almost certainly cost more than you planned.

These documents are not interchangeable. Here’s a quick breakdown.

SOW vs Proposal vs Master Services Agreement (MSA)

| Document | Primary Purpose | Level of Detail | Legal Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proposal | To sell services and persuade the client. | High-level overview of value and approach. | Generally not binding. |

| Statement of Work (SOW) | To define the specifics of a single project. | Extremely detailed with tasks, deliverables, and timelines. | Yes, it is a binding contract for a project. |

| Master Services Agreement (MSA) | To govern the overall legal relationship. | General terms, liability, and confidentiality. | Yes, it is a binding contract for the relationship. |

Each serves a specific purpose, but the SOW brings a project to life with clarity and accountability.

The Anatomy of a Bulletproof SOW

A strong Statement of Work isn't a wall of text. It's a collection of distinct parts that create a clear and legally sound project plan. Each section has a specific job, from explaining the ‘why’ to defining what ‘done’ looks like.

These sections are your defence against the assumptions that lead projects astray. Get them right, and you have a document that can guide decisions and settle disagreements. It's the difference between a project that runs smoothly and one full of "that's not what I meant" conversations.

The SOW sits underneath the broader Master Services Agreement (MSA) and works alongside the initial proposal.

The MSA sets the general rules for your entire relationship, while the SOW lays out the specific instructions for this project.

Introduction and Purpose

This is where it starts. The introduction briefly explains why the project exists. It’s not a marketing pitch; it's a concise statement that frames the business problem and the solution.

For a software project, it might be: "This project will develop a customer relationship management (CRM) module to automate sales lead tracking, cutting down manual data entry by an estimated 80%." That sentence sets the stage for everything else.

Scope of Work

This is the most important section of the entire document. The Scope of Work details every single thing that will be done. Here, you list all the tasks, activities, and processes needed to complete the project. Specificity is your best weapon against scope creep.

Just as important is listing what's out of scope. Stating what you won't do is as important as stating what you will. For instance: "This SOW covers front-end user interface development but excludes any back-end database architecture, which will be handled by the client's internal IT team." For more, check our guide on managing scope in a project.

Period of Performance

This section locks down the project timeline. It needs a clear start date, an end date, and any other time-based deadlines. It puts a fence around the engagement.

A clear Period of Performance stops projects from dragging on. It can be a simple statement: "The period of performance for this project will begin on 1 October 2025 and conclude on 31 March 2026."

Deliverables and Milestones

Here you list the tangible things you'll be handing over—the deliverables. These are the specific outputs the client is paying for. Each deliverable should be tied to a milestone, a key checkpoint in the project's timeline.

- Deliverable Example: "A fully functional user authentication module."

- Milestone Example: "User authentication module delivered to the client for review by 15 November 2025."

This structure breaks the project into manageable chunks and creates obvious points to track progress.

Acceptance Criteria

How will everyone agree when a deliverable is finished and up to standard? That's what this section is for. Acceptance Criteria are the objective, measurable conditions that must be met before a deliverable is signed off.

Vague goals like "a user-friendly interface" are useless here. You need specific, testable statements, such as: "The system must successfully process 100 concurrent user logins with an average response time of less than 2 seconds."

Without sharp criteria, 'done' becomes a matter of opinion—a fast track to a dispute.

Payment Terms and Schedule

This section outlines the financial agreement, detailing the total project cost and the payment schedule. Smart SOWs link payments directly to the milestones you've already defined.

A common setup is milestone-based payments:

- 25% of the total cost is due when the SOW is signed.

- 25% is due when Milestone 1 is successfully completed.

- 25% is due when Milestone 2 is successfully completed.

- The final 25% is due upon project completion and final sign-off.

This approach ties payment to progress, which keeps things fair for both sides.

Reporting Requirements

How will you keep everyone in the loop? This section establishes the communication plan, specifying how and when you’ll report on progress. It’s about keeping stakeholders informed and avoiding surprises.

You’ll want to define:

- Frequency: Will reports be weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly?

- Format: Will it be a formal document, a dashboard update, or a standing meeting?

- Content: What key performance indicators (KPIs) will you track?

It can be as straightforward as: "The project manager will email a written status report to the client sponsor every Friday by 5:00 PM CET." This detail keeps communication structured and professional.

Writing SOWs for Technical Projects

Drafting an SOW for a technical project is different. When you build a physical object, specifications are often fixed. Software and IT projects are fluid and full of unknowns. A generic SOW leads to misaligned expectations, blown budgets, and a final product that doesn’t solve the problem.

The trick is to shift from describing rigid processes to defining measurable outcomes. A good technical SOW gives the team enough detail to know the goal, but also enough flexibility to solve problems and adapt. It’s a balance between precision and practicality.

From Vague Ideas to Concrete Deliverables

In a technical project, ambiguity is the enemy. A phrase like "build a login system" is almost useless in an SOW because it leaves too much open to interpretation. What does that mean?

You have to break it down into specific, testable components. A better approach is to define the deliverable as a "user authentication module." That change in language forces you to think through its specific functions.

A strong SOW would get even more specific:

- Authentication Methods: The module must support standard email/password login and OAuth 2.0 with Google.

- Password Requirements: Passwords must meet PCI DSS complexity standards, including a minimum of 12 characters, one uppercase letter, one number, and one special character.

- Security Features: The system will implement two-factor authentication (2FA) via an authenticator app and include brute-force attempt lockouts after five failed login attempts.

- Performance: The module must authenticate a user and generate a session token in under 500 milliseconds.

This level of detail leaves no room for guesswork. The development team knows what to build, and the client knows what they’re paying for. This process is part of creating a larger project plan, which you can learn more about in our guide on work breakdown structure examples for project management.

Defining Acceptance Criteria in Agile

Agile development complicates traditional SOWs. How do you define the entire scope upfront when agile is about being iterative? The answer is to focus on user stories and performance metrics as your acceptance criteria.

Instead of listing every feature from day one, you can define acceptance criteria for individual sprints or key deliverables.

Acceptance criteria for technical projects should be written as testable conditions. If you can't write a pass/fail test for it, the criterion isn't specific enough.

Here are a few examples of turning vague requests into solid criteria:

| Vague Criterion | Specific, Testable Criterion |

|---|---|

| "The dashboard should be fast." | "The main user dashboard must load all data widgets in under 3 seconds on a standard broadband connection (100 Mbps)." |

| "Users can search for products." | "As a user, I can search for products by name, SKU, or category, and the results must return within 1 second for a database of 1 million products." |

| "The API must be secure." | "The API must pass a third-party penetration test with no critical or high-severity vulnerabilities identified." |

This approach lets your development team work within an agile framework while being held accountable to the measurable outcomes in the SOW.

Security and Compliance Protocols

Forgetting to detail security and compliance requirements in an SOW is a massive risk. These are not afterthoughts; they are core project requirements that need to be included from the beginning.

Your SOW should explicitly state which standards the project must meet. This section needs to cover:

- Data Handling: Specify how personally identifiable information (PII) or other sensitive data will be stored, encrypted, and transmitted.

- Compliance Standards: Clearly state if the project must be GDPR, HIPAA, or SOC 2 compliant.

- Security Audits: Detail any requirements for code reviews, vulnerability scans, or mandatory third-party penetration testing.

Including this ensures the final product is secure and compliant and forces you to allocate time and budget for these activities in the project plan.

External legal factors also matter. For example, Dutch employers are preparing for new wage transparency mandates in 2026. Firms with over 100 employees will have to report on gender pay gaps. Any IT project involving HR or financial systems will need to account for this. You can read more about these upcoming changes for Dutch employers on flib.nl. This is an example of how outside regulations must be considered when scoping technical work.

Adapting Your SOW for Modern Work Arrangements

The nine-to-five office model is fading. Today’s projects often involve a mix of full-time staff, part-time specialists, and independent contractors collaborating from different locations. This reality demands a more flexible SOW.

Trying to use a generic SOW built for an on-site workforce with a distributed team is a mistake. It creates confusion over availability, opens the door to scope creep with contractors, and can cause legal problems. Adapting your SOW is necessary for managing risk in today's work environment.

Shifting from Hours to Outcomes

When working with part-time or contract talent, billing by the hour can be inefficient. A modern SOW should pivot from tracking time to defining clear, measurable outcomes. The focus needs to be on what gets delivered, not how long it took.

This approach gives contractors the freedom to work on their own schedule while holding them accountable for the final product. It also simplifies project management by cutting down on tracking fractional hours.

For instance, instead of stating "15 hours per week for social media management," a stronger SOW would define the result you're paying for:

- Deliverable: Five unique, approved social media posts for LinkedIn, published weekly.

- Metric: A minimum 2% engagement rate per post within the first 72 hours.

- Reporting: A weekly performance report delivered every Friday by 5 PM.

Managing Scope with Temporary Staff

Short-term contractors are brought on for their specific expertise. Without a solid SOW, their roles can bleed into other areas, stretching your budget and timeline. The scope section for contractors needs to be precise. It must clearly outline what they are responsible for and what falls outside their engagement.

An outcome-based SOW for a contractor isn't about micromanaging their time. It's about clearly defining the finished product you're buying so there are no disputes about what 'done' means.

This clarity protects everyone. The contractor knows what's expected, and you get what you paid for. No awkward conversations or surprise invoices. You can explore different ways of measuring the impact of hybrid work to see how these defined outcomes contribute to the bigger picture.

Navigating False Self-Employment Regulations

Bringing in contractors requires careful legal planning, especially in regions with strict labor laws. An improperly worded SOW can accidentally create false self-employment (or schijnzelfstandigheid), where a contractor is legally seen as an employee. This can expose your company to legal and financial penalties.

Your SOW must avoid language that suggests an employer-employee dynamic. That means:

- Avoid specifying exact working hours or a mandatory location.

- Do not dictate the specific methods or tools a contractor must use.

- Focus entirely on the final deliverables and deadlines, not on day-to-day task management.

The Dutch labor market is an example of this tightening landscape. Recent regulations targeting false self-employment have caused a shift, with 54% of former freelancers moving into permanent or temporary contracts. This trend is part of a wider market adjustment expected to delay a full staffing recovery until 2026, as detailed by analysts at think.ing.com. For project managers, this means being more precise than ever. By building your SOW around independent deliverables, you maintain a clean, compliant line between contractors and employees.

Common SOW Mistakes That Wreck Projects

A project’s fate is often sealed long before any work begins. It happens when drafting and reviewing the SOW. A poorly written SOW isn't just a document with typos; it’s a blueprint for conflict, missed deadlines, and wasted money.

These are not theoretical problems. They are recurring failures that turn promising projects into messes. Avoiding them starts with knowing what they look like.

Vague Language and Undefined Terms

The biggest mistake is ambiguity. Phrases like "a user-friendly interface" or "robust back-end services" sound professional, but they mean nothing without concrete definitions. This vagueness creates a gap between what the client expects and what the provider intends to deliver.

This is the root of most project disputes. When key terms are subjective, success becomes a matter of opinion, not a measurable outcome.

Scenario: The 'Unlimited Revisions' Trap A marketing agency’s SOW promises "logo design concepts with revisions." The client interprets this as endless tweaks, while the agency assumes two rounds are standard. Weeks are lost in a frustrating cycle of feedback, blowing the timeline and poisoning the relationship.

The solution is to be specific. Replace fluffy adjectives with hard numbers and testable conditions. Every key term in your SOW, from "completion" to "support," needs a clear definition.

Missing or Weak Acceptance Criteria

How do you know when a deliverable is done? Without clear acceptance criteria, you don't. This section is often rushed, which is a critical error.

Weak criteria turn the project sign-off into a negotiation instead of a verification. It leaves both parties vulnerable—the provider to endless change requests and the client to a half-baked product.

- Weak Criterion: "The new software module will be tested."

- Strong Criterion: "The software module will pass all 47 predefined user acceptance tests (UAT) documented in Appendix B, with a maximum of 5% non-critical bugs, before being considered complete."

No Clear Change Control Process

Projects change. An SOW that doesn't anticipate this is flawed. Without a formal change control process, small requests and "quick adds" pile up, leading to scope creep.

This process doesn't need to be complicated. It just needs to be documented and followed. It should outline how a change is requested, how its impact on cost and timeline is assessed, and who needs to approve it in writing. This transforms "Can you just add..." from a casual question into a formal business decision.

To help ensure your SOW avoids these pitfalls, it's worth reviewing common errors in similar documents. This guide on 10 common mistakes in proposal writing is a good place to start, as many of the same principles apply.

Unrealistic Timelines and Resource Allocation

Optimism is not a project management strategy. An SOW might set an aggressive timeline to win a bid, but it sets the project up for failure. It ignores dependencies, team capacity, and the fact that unexpected issues always come up.

A common oversight is resource planning, especially with non-standard work arrangements. In the Netherlands, nearly 60% of women in the labor market work part-time. This impacts everything from project velocity to software license management. Your SOW must accurately define full-time equivalents (FTEs) to set a schedule that reflects how people actually work.

The fix is to build the schedule based on a detailed breakdown of the work, consulting with the people who will be doing it. A realistic timeline isn't pessimistic; it's professional. It builds trust and makes success achievable.

Your SOW Questions, Answered

Even with a good template, real-world questions come up when you write an SOW. Here are some of the most common ones.

Who Actually Writes the Statement of Work?

In most cases, the service provider or agency drafts the first version. They are the experts on the service, so it makes sense for them to lay out the tasks, deliverables, and timeline.

But that's just the start. An SOW should be a collaborative document. The client has to ask hard questions and push for changes until it matches what they need. Usually, the project manager on the provider's side leads the process, pulling in legal and technical people.

On the client’s end, the project sponsor and the department head need to review it. Never just sign an SOW as-is. Get all your stakeholders to read it first.

What Happens When the Project Changes After We’ve Signed?

Projects change. A well-crafted SOW is built for this and includes a "Change Control Process" section.

This part of the document lays out the exact steps for handling any requested change. Typically, it involves filling out a formal Change Request form. This form isn't just bureaucracy—it forces everyone to detail the proposed change and its impact on the project's scope, timeline, and budget. Both sides have to sign off on this form before any new work begins.

Think of this formal process as your best defence against scope creep—that undocumented expansion of a project that blows up budgets and deadlines. It turns a casual "Could we just add...?" into a deliberate business decision.

Is a Statement of Work a Legally Binding Contract?

Yes. Once signed by people with authority from both companies, an SOW becomes a legally binding contract. It holds both parties accountable for the obligations, responsibilities, and deliverables for that project.

It often works with a broader Master Services Agreement (MSA), which handles the general legal terms of the business relationship. The SOW then fills in the project-specific, enforceable details. If a dispute arises, the courts will look to the SOW to see what was agreed upon.

How Detailed Does the Scope of Work Need to Be?

Getting the Scope of Work section right is a balancing act. You need enough detail to prevent confusion, but not so much that you handcuff the provider and stop them from using their expertise.

A good rule of thumb is to focus on the 'what' (the outcome) and not the 'how' (the specific method). The exception is if the 'how' is a critical technical or legal requirement. For example, specify 'the system must handle 5,000 transactions per minute,' not which programming language they have to use.

One of the most powerful things you can do when defining scope is to also define what's out of scope. Stating what the project will NOT include is a simple but effective way to head off wrong assumptions.

For example, a single sentence like, "This project covers the user interface design but explicitly excludes back-end server configuration," can save you from a massive headache down the line.

Gain real-time visibility into how your teams actually use their software and tools. WhatPulse provides privacy-first analytics to help you optimise software spend, manage IT resources, and understand work patterns without compromising employee trust. See how your work happens at whatpulse.pro.

Start a free trial